Leadership & Management

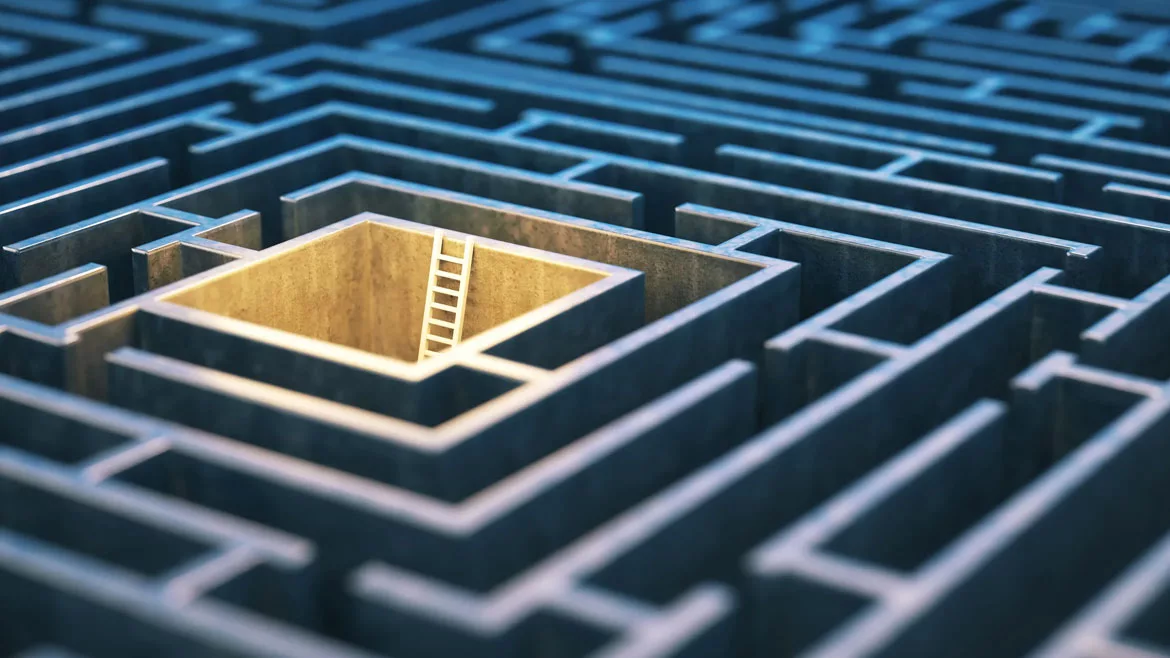

Escape Rooms, Mud Runs, and Game Nights: Cradles of Leadership?

What team-building games can teach us about real leadership.

When a soft-spoken, strictly nine-to-five administrator joined our department’s escape-room outing, no one expected much. She was polite, precise, and reserved. Yet, minutes into the challenge she came alive. She assigned roles, organized clues, and kept everyone focused as the clock ticked down. She even cracked the hardest puzzles. We escaped the mad scientist’s lab with minutes to spare.

Here was leadership potential that had never surfaced at the office. On the strength of that performance, and after talking with her manager, we promoted her to a supervisory role.

It was a disaster.

She hated managing others, attending meetings, and staying late. The spark that blazed in the escape room dimmed under the fluorescent light of responsibility. Eventually we moved her back to her old job, where she again thrived and left at 5:00 p.m. on the dot.

The experience raised a question: Should we scout for leaders outside traditional work settings — softball games, puzzle tournaments, mud runs, or escape-room outings? What do those experiences truly reveal about leadership, and when do the skills translate?

Escape rooms are miniature laboratories of organizational life: limited time, ambiguous information, shared goals, and diverse personalities. Some players leap into command. Others observe quietly until they find a way to add value. The teams that succeed are not led by the loudest voice but by the one who synthesizes input, keeps calm, and values everyone’s contribution.

“These kinds of activities can be fun, energizing, and great for team camaraderie,” says executive coach Jon Bassford. “They can showcase problem-solving and create opportunities for people to step up. But they can also unintentionally reward charisma over capability. Too often, leaders confuse Type A personalities with A players.”

The key, Bassford adds, is thoughtful debriefing: “Who helped align the group? Who listened before acting? Who adjusted course when new information emerged? The real value comes in reflection, not the game itself.”

Luca Tenzi, a Swiss-based security leader who has managed teams across three continents, sees these settings as windows into employees’ whole selves.

“One of the main challenges,” he says, “is that people have multiple lives. They do their job by day, and at night they wear a superhero suit. In an escape room they’re not in an office context. They feel they can shine and take a leadership position.”

At work, culture and expectations often mask natural behavior. “The only way to know someone is a natural leader is to observe them outside work,” Tenzi says. “Where I’ve failed a few times was when I didn’t see them beyond the office.”

Still, he cautions against overreach. “Some people don’t want you to see who they are in the rest of their lives,” he notes. You have to respect boundaries of culture, religion, and identity. “Leadership is measured by understanding the whole person, not just what you see in one setting.”

Tenzi also warns against forcing leadership where it doesn’t belong. “You can’t always create a good leader. …To make someone shine, you must create the right conditions.”

Lee Oughton, VP of LATAM Operations at Concentric, echoes that view. “The culture is the heartbeat of every organization,” he says. “I look for people who will go the extra mile for others. I’ve always identified strengths and weaknesses, mine first. If I’m bad at something, I don’t waste time trying to perfect it. I find people whose strengths complement mine.”

Oughton’s insight reframes the idea of finding leaders. Real leadership, he argues, is not about domination but elevation, about those who make others better. Observing who enables teammates to succeed may tell you more than watching who takes charge.

For Malcolm Smith, a South Africa–born security executive now based in Saudi Arabia, leadership discovery is both art and experiment. “I’ve learned from Marshall Goldsmith that leadership is a contact sport,” he says. “There’s no exact science in promoting potential leaders. Every promotion brings some level of incompetence. Moving your employee back into the role where she thrived was the right call. Others only perform better once they’re given the right development. That’s called learning to fly on the way down.”

Smith believes growth requires both support and willpower. “Good mentoring and coaching help, but it depends on the person’s willingness to learn and grow. Don’t waste time coaching someone who doesn’t want to change. A leader of the past knows how to tell; a leader of the future knows how to ask — for help, for answers, for new ideas.”

Smith’s final question reframes the whole issue: “Does a nine-to-five employee lack commitment, or just work differently? Some cultures prize visible endurance; others value balance. Working longer hours doesn’t always signal leadership; sometimes it signals an inability to delegate.”

In hindsight, my biggest gift to my escape-room-expert Houdini was to give her the key to her former job.

As Tenzi puts it, “Leadership isn’t about making everyone perform the same way. It’s about understanding what environment brings out the best in each person.” And as Smith reminds us, “Every leader learns to fly differently, but you only see their wings when the fall begins.”

In other words, in an escape room, as in any organization, the best leaders aren’t necessarily those who hold the key, but the ones who help everyone else find it.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!