Special Report

Strategies for supporting security teams

Creating effective teams can only be achieved when leaders carefully build a culture of support.

scyther5 / iStock / Getty Images Plus / via Getty Images

To counteract the effects of COVID-19, security leaders have refocused their attention on vital organizational pillars — workforce planning, training, budgets and policy — modifying their leadership approach to enable effective support for their staff. This new leadership philosophy is critical to aid exhausted staff after years of struggling with pandemic-related financial pressures, strained resources, staff cutbacks, juggling work and family responsibilities, and other life stressors.

Supporting teams in the security industry is especially important because security is a service industry, says Ricardo Segovia, Global Security and Resiliency Manager at Google. “It’s not unusual to work alongside highly motivated folks who will do anything to get the job done,” he explains.

Security programs are only as good as their people, and leaders are only as successful as their teams. So, if teams are disengaged and burning out because of increased workloads, poor management or lack of support, it tends to have a ripple effect across the organization. Leaders will be left with a stagnant security program, ill-equipped to fulfill the core mission of protecting the business.

“This is why fostering a culture of support and psychological safety where people feel comfortable sharing is so important,” Segovia says. “This is perhaps one of the most difficult tasks leaders have, as it requires leaders to constantly scan for signals to assess the teams’ well-being.”

While support can take many shapes and forms, leaders should evaluate each person’s needs and wants, as well as the social context in which situations occur, Segovia says.

*Click the image for greater detail

What Support Looks Like

So, how can leaders ensure that they are effectively supporting their teams? Security leaders say it takes a combination of leading by example, encouraging work-life balance, prioritizing mental health, and practicing empathy to truly create a culture of support.

Josh Yavor, Chief Information Security Officer at Tessian, changed his view of leadership due to his own burnout and now is an advocate for work-life balance. While he faults himself for not identifying his burnout earlier on, he credits himself for ripping the Band-Aid off and going through a deeply uncomfortable process to reverse burnout. The process included leading by example, informing his team of when he would sign off, and not sending Slack messages or emails after hours. “I showed I was accountable for maintaining a better work-life balance and communicating and demonstrating what that looked like by setting healthy boundaries,” he shares.

While it caused much angst on his end and across his team when Yavor stopped producing the same volume of work, he was able to help others communicate better on work and delivery expectations as a result. “Learning to have uncomfortable but necessary conversations and creating a central and clear list of priorities helped set up my future teams for success,” Yavor says.

For Eddie Reyes, Director of the Department of Public Safety Communications of Prince William County, Virginia, who has led his 911 dispatch team through the pandemic, encouraging work-life balance was a must, particularly to tackle hiring and retaining challenges. “In 911, there’s much greater risk involved in not keeping our seats occupied. For us, answering calls promptly is a matter of life and death.” Recruitment and retention are so top of mind that Reyes has a weekly staff meeting with senior staff to directly address this challenge head-on.

To help increase retention and hiring and keep team morale at the highest level, security leaders are focusing on simple but effective measures. For Reyes, this includes making the environment as friendly and professional as possible. The Prince William County Department of Public Safety Communications has a state-of-the-art center with new technology and furnishings. “It’s a great place to come to work. Employees are not in a dimly lit dungeon or in the basement with no windows. It is warm and inviting,” he says.

To keep staff engaged, Jeffrey Hauk, Director of Public Safety at Memorial Healthcare, has made it a point to make sure security staff take regular breaks throughout shifts, particularly when eating. “We expect them to take breaks during the day to decompress, especially if there are stressful incidents security has dealt with,” he says.

Alongside the importance of daily breaks, Reyes says the department tries to satisfy team members with time off requests. For those struggling with a personal or stressful situation, such as handling a call for service involving a death that emotionally drains one of his team members, Reyes has two procedures in place: timeout and a peer support team. “We have this expectation that if an employee is dealing with a traumatic situation, they have to get back in shape, emotionally unplug, and recover,” he says. “Only then can they come out on the floor.”

If the staff member shows signs of distress or severe trauma, Reyes has a peer support team to alleviate those situations. The peer support team can triage the situation at their level or elevate it to mental health clinicians.

Mental Health

Mental health in the workplace is an urgent priority. Several security leaders are stepping up their leadership to acknowledge mental health and opening the door to address employee wellbeing.

Reyes tells the story of an employee who took a “mental health quarter” to recover and recharge. Allowing this employee to leave for three months and prioritize mental health wellness — because she was a valued employee — allowed the department to retain top talent. “Pick your poison,” Reyes says. “Can you live without them for three months? Or can you live without them forever?” Security leaders should emphasize to employees that there are no repercussions for asking for help, he adds.

At Cardinal Health, John Rodriguez, Director of Global Security, is proud of establishing a program called Community Conversations on Mental Health. While not required, any employee can join a session on Zoom, share their own experience with mental health, and obtain the help they need to improve coping abilities to manage stress, anxiety and depression. The program has grown so much that Rodriguez and his team are training at the corporate level. “We are establishing a culture based on trust and creating a program that helps destigmatize mental health,” he says. “It also impacts engagement, reduces presenteeism, turnover and sick days, and helps attract and retain quality talent.”

For Hauk, the continuous challenges during the pandemic have solidified that mental health needs to be a key priority for every security leader. “Even when we get on the other side of the pandemic, learning to talk about wellness during regularly scheduled and not scheduled meetings, prioritizing the monitoring of our team’s mental health, and incorporating wellness practices to ensure teams have the support and resources they need will be critical moving forward,” Hauk says.

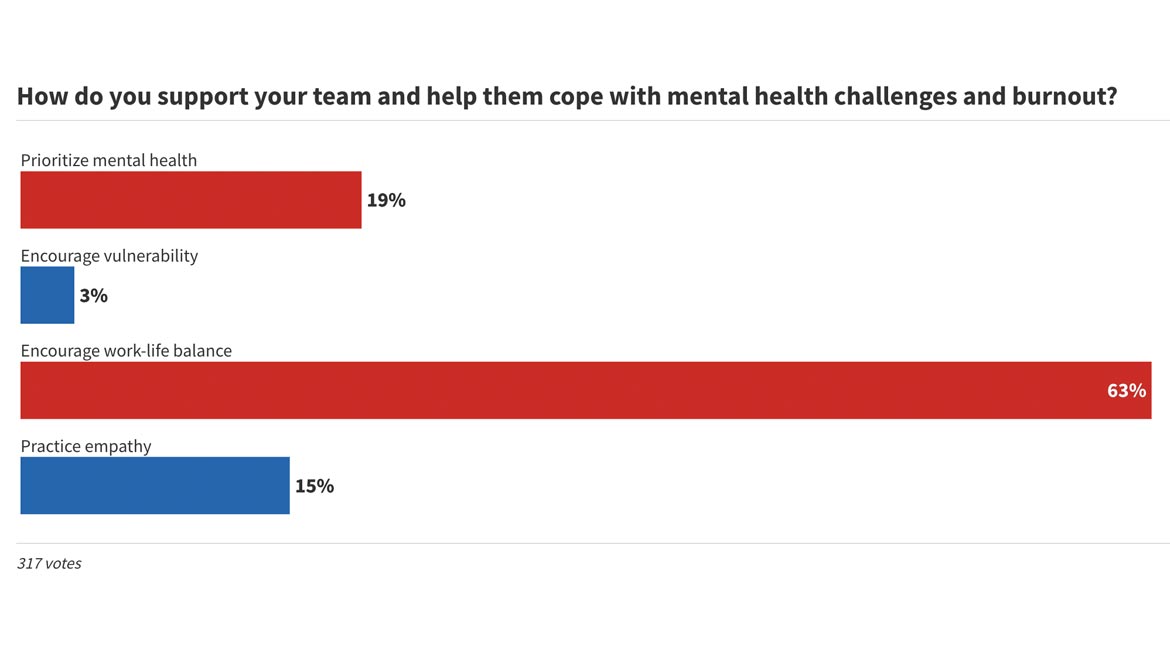

To gauge how security leaders support their teams to mitigate challenges to team wellness, Security magazine polled security professionals on LinkedIn.

To gauge how security leaders support their teams to mitigate challenges to team wellness, Security magazine polled security professionals on LinkedIn.

*Click the image for greater detail

Empathy

In addition to encouraging mental wellbeing, practicing empathy is a critical part of supportive leadership. An empathic leader makes employees feel safe and taken care of within their organization, leading staff to feel a sense of trust and belonging within the team and the organization. Practicing empathy is fundamental to achieving a highly effective, motivated and high-performing team.

To many security leaders, this is perhaps the most critical and challenging aspect of all. While leaders can have the intention of having a distinguished security culture, overall corporate culture needs to be based on empathy as well, Rodriguez says. “Some leaders are numbers-driven, and they’re under pressure to obtain metrics, so some lead by mandate, versus creating a culture where empathy is part of the team DNA as well as ensuring the corporate and security mission,” he says.

Practicing empathy is also challenging because it requires security leaders to go well beyond duties as a people manager. “Leaders need to understand who team members are as individuals before anything else, while also reflecting on their views and experiences, not yours. Empathy is about gaining insights through total immersion in other people’s experiences,” Segovia says.

Listening and taking a personal interest in staff lives can go a long way in being an empathic leader. “Go back to the basics. Make it a true priority to go out of your way several times a week and meet security staff where they are. Listen to their concerns, hopes and ideas. Lastly, ask staff how you as a leader can continue to be a resource for them to be successful at their jobs,” Hauk suggests.

Reyes says that anyone can train and practice to become more empathic. “It starts at the top, and if you have a leader that’s not practicing empathy, this behavior starts to spread like a plague. Commit to empathy as a rule and care about people, not simply what they offer to your team,” Reyes says. “For us, we are a working family. If we can’t help each other, we can’t fulfill the organization’s mission.”

Editor's Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and interviewees and do not necessarily purport to reflect the opinions or views of Alphabet Inc. or its entities.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!