COVID-19 Heroes

Georgetown University’s Office of Emergency Management supports COVID-19 response

Marc Barbiere came to Georgetown about five months before the COVID-19 pandemic, taking over the recently-restructured Office of Emergency Management (OEM) in order to coordinate the University’s efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from emergencies.

Georgetown set up aggressive COVID-surveillance testing, daily symptom checks, building access restrictions and more as a part of their pandemic response efforts.

Image courtesy of Georgetown

Marc Barbiere, Director of the Office of Emergency Management, Georgetown University.

Image courtesy of Barbiere

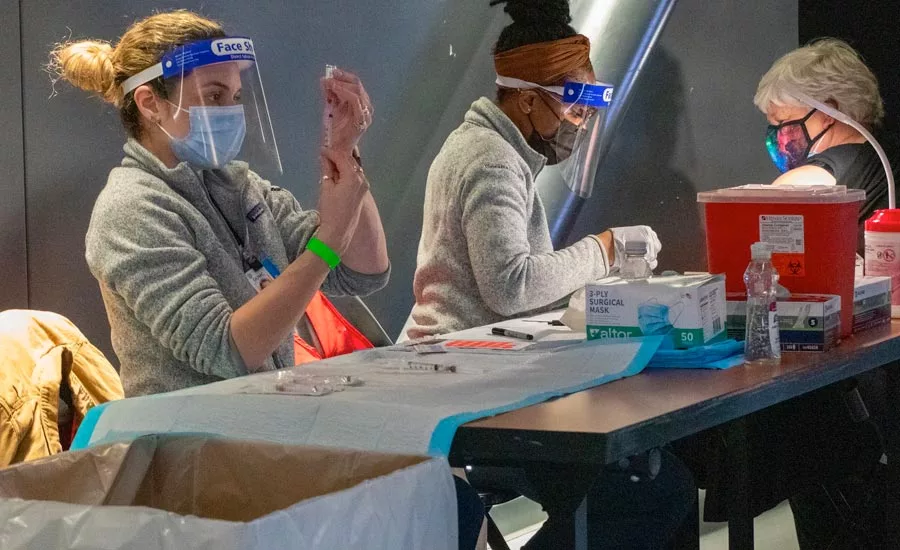

Image 3a: Many staff and students volunteered or were re-deployed to help with pandemic response efforts including contact tracing, testing and vaccine efforts.

Image courtesy of Georgetown

Image 3b: Many staff and students volunteered or were re-deployed to help with pandemic response efforts including contact tracing, testing and vaccine efforts.

Image courtesy of Georgetown

Image 3c: Many staff and students volunteered or were re-deployed to help with pandemic response efforts including contact tracing, testing and vaccine efforts.

Image courtesy of Georgetown

Marc Barbiere had only been at Georgetown University (Georgetown) a couple of months before the COVID-19 pandemic started. He was still learning about Georgetown’s operations and governance structure as he took the helm as Director of the Office of Emergency Management. But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t ready.

Barbiere has been through many large-scale emergencies, including 9/11, flu vaccine shortages, a steam pipe explosion, collapsed cranes, H1N1, Ebola, and numerous severe weather incidents to name a few. He made the jump into emergency management in 2003, but prior to that, he was an NYC EMS paramedic and a NYC Fire Department EMS Lieutenant. On the public health side, he held leadership positions with the NYC Department of Health, the Fairfax County Health Department’s emergency preparedness program, and the D.C. Department of Health, as well as having served as an emergency manager in the Austin, Texas area, before coming to Georgetown in November of 2019.

His background as well as his Master’s degree in Public Health allowed Barbiere to hit the ground running in regards to COVID-19 response at Georgetown. About a month into his new position, Barbiere began paying attention to a potential health crisis with wide ramifications. Soon after that and well before COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic, Barbiere and his colleagues began to assemble a team of key stakeholders and started collaborating with the D.C. Department of Health to focus on emergency preparedness and prepare the University for potential effects.

“We had staff and students around the world in Europe, China, Korea and more, and we acted early and aggressively to ensure everyone was safe” Barbiere says.

By February, the emergency management team at Georgetown was conducting pandemic-related tabletop exercises, with important stakeholders brought in to be a part of the process, including representatives from the various campuses and schools, as well as public health subject matter experts (SMEs) and global experts.

“I wasn’t the smartest person in the room, but we are fortunate to have some of the best SMEs right here on campus,” Barbiere says. With 50-60 people around the table, the exercises allowed the team to look at COVID-19 through various phases and scenarios.

When March 2020 came around, the Mayor declared a state of emergency and in-effect shut down D.C., and Georgetown went virtual, including its emergency response activities. Throughout the past year, Georgetown has continued planning and holding tabletop exercises, putting stakeholders through different phases and worst- and best-case scenarios to prepare the entire campus community, including a planned complete reopening in the fall of 2021.

To truly streamline a coordinated response effort, Barbiere has been deliberate since the early days of the pandemic to develop, maintain and encourage various working groups within Georgetown, made up of stakeholders from a range of departments such as Facilities, Residential Living, Auxiliary and Business Services, Communications, and the Police Department among others. Together, the groups participate in planning meetings and tabletop exercises, sharing ideas, information and decisions.

There were a number of hurdles Barbiere and Georgetown had to jump over in regards to COVID-19, not the least of which was responding to a global pandemic, while also trying to focus on building up the newly restructured Office of Emergency Management itself. “Many of those routine emergency management duties that we would have done right away, such as performing risk assessments, updating training and response plans, were put on hold,” Barbiere explains. In addition, “As a large educational organization, we also have a lot of very broad and independent silos on both the academic and operational side, so it took time to develop a cohesive structure for dealing with emergencies and getting the right people together at the right time to pivot to respond. At first, it was pretty painful and clumsy; it took time for us all to get to know one another.”

But the Georgetown team persisted, planning regular meetings and check-ins that Barbiere says will ramp up or down depending on what the University is preparing for and the current circumstances of the pandemic.

Georgetown has set up aggressive COVID-surveillance testing, daily symptom checks, building access restrictions and more as a part of their pandemic response efforts. One of the groups Barbiere and Dr. Ranit Mishori, the Chief Public Health Officer, put together and led as part of the University’s multi-layered approach to ensuring health and safety is the Care Navigator team.

The group has been very effective at protecting the community and reducing the impact of COVID-19 to the campus and greater D.C. community as much as possible. Part of the role of the Care Navigators is what Barbiere refers to as “contact tracing on steroids.” The team supplements the efforts of the D.C. Department of Health, investigating potential contacts within the University if someone tests positive for COVID-19 and investigates the potential on-campus risks.

At the height of the pandemic, Georgetown had about 30 team members on the Care Navigator Team, many of whom were existing staff members that were re-deployed to work on pandemic response efforts. “We put them through Johns Hopkins contact tracing training and other university specific training. They not only work with students, faculty and staff that test positive for COVID-19, but they also coordinate food delivery, isolation moves, and more,” Barbiere says.

Now that Georgetown is gearing up to open fully for in-person classes this fall, Barbiere says the re-deployed employees are in the process of moving back to their previous positions. The Care Navigator team has been so successful at helping with response efforts, however, that Barbiere sees a smaller version of this crew (on a contracted basis as well as to include continuing redeployed staff) staying on into the future to help with whatever response efforts are needed.

“We are in the process of building this capability on a permanent basis as we anticipate another six months to a year or so of COVID-related activity, and then eventually to be a part of the public health structure to deal with pandemics and public health emergencies in the future,” he says.

Using his deep connections have also benefitted Georgetown, as Barbiere has been one of the primary liaisons with the D.C. Department of Health and other agencies during the pandemic. The partnership has been beneficial to both the Georgetown community as well as the greater D.C. community. The University operated a public vaccination clinic early on, tapping into its wealth of medically trained volunteers and staff to vaccinate community members, including frontline healthcare workers and vulnerable populations.

“Now that the vaccine is ubiquitous, the Department of Health has started providing us with vaccines to distribute on our campuses for our own population,” Barbiere says. The efforts come at a good time, as the University has decided to mandate vaccinations for students, faculty and staff this coming fall, and Georgetown will use its on-campus clinics to help with the efforts to get to that goal.

It’s those relationships, according to Barbiere, that every seasoned emergency management leader knows are some of the most valuable tools in the toolkit when it comes to emergency response. “Building good productive relationships with preparedness partners before a disaster will serve you well in an emergency. One of the successes we have had here at Georgetown is the relationships that so many of us have locally and regionally and that’s what you need; to be able to share information and resources.”

Barbiere says that every security leader learns from each emergency and one of the things he believes the Georgetown team has learned is how to communicate across cross-functional areas of the organization.

“We worked together here and forged strong relationships that will serve us immensely in preparing for responses big and small in the future. We will certainly face other threats as an organization, but we will come together and those lessons will help us in the future,” Barbiere says.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!