2011 Security Leadership Issue: Like Risk, Security Leadership Success Is a Moving Target

|

Since the Security Executive Council launched six years ago, it and its research arm, the Security Leadership Research Institute (SLRI), have studied the shifting shape of the security profession and its drivers. Through in-depth, ongoing research, development of the Collective Knowledge™ process, and trend tracking, we have learned much about the changes that have affected security, as well as the personal and external factors that help determine leadership success.

Risk Is Not Universal

One thing our research has clearly shown is that there are no universally perceived risks. While there are certain risk categories that tend to apply to many businesses in some form, it is both difficult and unwise to try to tie “business risk” into a neat bundle and assume it applies equally to every organization.

In the last 10 years, globalization and virtualization have played major roles in increasing the complexity of businesses in every market. We have seen fundamental changes in how we do business, and those changes impact how we view and respond to risk. Unless we have another national crisis, the risks to watch now and in the near future will be sector-specific and organizational in nature.

In fall 2009, the SLRI found that regulations and compliance took the top spot when security practitioners were asked to identify the top five risks to their organizations. For companies with international business, one regulation of concern may be the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; for the financial industry it may be the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act; for chemical it may continue to be the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards.

Intellectual property risk came in first only in similar research conducted for the Security Executive Council Tier 1 Security Leader community. In the pharmaceutical industry this risk may manifest in counterfeiting of drug products, diversion of assets and the brand problems that may result. In another industry – defense, for example – loss of intellectual property may mean theft of blueprints by competitors or state-sponsored spies.

Business continuity also ranked in the top five for both the Tier 1 and broader security communities, and its significance has once again grown in light of recent natural disasters and other events. Clearly business continuity is on the mind of senior management right now, but that brings us to another risk: the whims and perceptions of senior management.

|

The Threat of Under-informed or Misinformed Management

Risk is still developing as the common language of the corporation. Since September 11, 2001, senior management has increasingly kept “security” in its sights; enterprise risk assessments, 10-K risk statements and business continuity planning all have management’s attention. This is both a blessing and a curse.

It’s undeniably positive that senior managers are showing interest in the risk posture of their organizations. This increases the potential for security leaders to provide input at the highest levels of the company to better mitigate risk. However, Security Executive Council trend tracking shows that in many cases the interest that senior management shows is not a steady, measured examination of risk; it is a short-term, knee-jerk reaction to current events and immediate shareholder fears.

In the largest sense, risks haven’t changed. Business continuity risk existed 10 years ago, and 20, 30 and 40 years ago. Japan did not experience the first earthquake in history this year, nor the first tsunami, but many businesspeople are acting as though that’s exactly what it was. Management becomes aware of risks as incidents and media exposure brings them to the fore, and then they often over-address those risks in the short term, neglecting or damaging other risk mitigation programs in order to do so. Before long, the risk of the day is forgotten until another incident brings it up again. In cases like these, senior management desires to appear risk conscious, but upon deeper examination they can’t be described as such.

Security Executive Council research has found that one of security leaders’ biggest fears is that management doesn’t understand the risks that exist beyond the latest headlines—the ones that pose a long-term, potentially damaging threat to the company. Thus, they fail to support mitigation with their influence and with budget allocations, leaving the company vulnerable and making it impossible for the security leader to effectively manage risk.

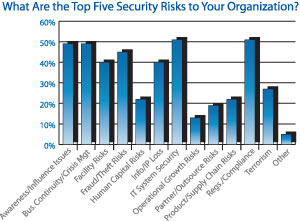

In 2008, the SLRI found that getting management support for countermeasures to identified risks was the second-highest priority of responding security leaders. See “What Are the Top Five Security Risks” chart elsewhere in this article. (Ironically, the first was doing more with fewer resources.) Security still struggles to gain management support in spite of its increased visibility as a business issue, and even when risk is understood, security’s value often is not.

Communicating Value

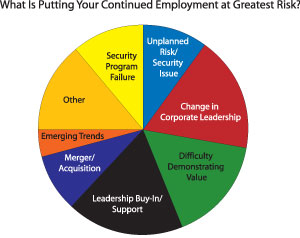

In May 2009 the SLRI asked security practitioners, “What in your organization is putting your continued employment at greatest risk?” Two of the three top responses were an inability to demonstrate security’s value and lack of leadership buy-in. See the "Putting Continued Employment at Risk" chart elsewhere in this article. An understanding of risk issues isn’t the only thing security leaders are failing to convey to executives. Demonstrating security’s value is key to securing leadership buy-in, and it’s not happening.

“How do I communicate value?” “How do I get management to listen to me?” and “How can I get funding?” are still some of the questions we most frequently hear from security leaders. In many organizations the security leader is three steps removed from the C level, and he or she is not even given the opportunity to present to executive management on risks or security value.

Complicating this problem is the fact that corporate leadership in many industries has begun changing with more frequency than it did in years past. As leaders finally begin to get their foot in the door and gain influence with one CEO or CFO, that person uproots and the entire reporting structure is revamped under his or her replacement.

These situations present unique challenges to communicating risk and value, but security leaders bear part of the blame for the disconnect as well. In order to effectively communicate the value security brings to the organization, security leaders must truly understand the business and the priorities and goals of senior managers. As much as the security profession has advanced this decade, influence and communication remain major hurdles for many leaders. Too many focus on preventing incidents rather than delivering positive business results, and too few understand their businesses well enough to change that dynamic.

Knowledge and Attributes of a Successful Leader

Because security leaders continue to face this range of challenges, several of our major initiatives have attempted to find common elements that boost the probability of security leadership success. In 2006, our “Security Leadership Background Trends” study shed light on the backgrounds and knowledge many organizations have looked for in their security leaders over time. The study found that leaders with backgrounds in business were becoming the most sought-after candidates for top security positions. Observation since the study’s release has shown that this trend continues to grow. However, having a business background doesn’t necessarily increase the chances of success once the job is won.

Our background trends research led us to identify six skill sets that companies have looked for in their security leaders at various times in the last 50 years (the skills and backgrounds in demand tend to change with the events of the time): Government Elements, Security Organization Elements, IT Security Elements, Executive Leadership Skills, Business Elements, and Emerging and Horizon Issue Awareness. See the Next Generation Security Leadership chart elsewhere in this article. No one of these skill sets in itself will give the security leaders all the skills he or she needs to excel in today’s business environment; leaders must work to include all six skill sets in their security programs – either by honing their skills or hiring for the missing skills – for the best chance of success.

Adding to these findings, in 2009, as part of its Goals, Objectives & Strategic Plans project, the Council conducted in-depth interviews with 28 Tier 1 Security Leaders™ to discover and compare best practices. In analyzing these interviews, the Council identified nine commonalities among the highly successful, internally recognized security leaders.

The successful security leader:

• has created a robust internal awareness program for security, including formal marketing and communication initiatives

• ensures that senior management knows what security is and does

• has a walk-and-talk mentality – regularly talks to senior business leaders about their issues and how security can help

• converses in business risk terminology, not “security”

• understands his or her corporate culture and adapts to it

• is well respected and never reacts by exploiting fear, uncertainty and doubt

• has security program goals that mirror the company’s business goals

• has top-level support from day one

• sees security’s role as a bridging facilitator or coordinator across all functions.

The Criticality of Readiness

Some security leaders may look at the list above and say, “I’ve tried all that. I’ve tried to learn from all those skill sets, and I’ve tried to do all the things you describe. I’ve even been successful at many of them. But I still can’t get the funding I need. I still don’t have the influence I need to make security a true C-level concern.”

In this case, the organization may not be ready for a best-in-class security program. Leaders with all the skill sets and all the attributes may not get very far if they are working in an atmosphere of low organizational readiness for best-in-class security programs. For true alignment and the best chances of success, the organization, the security leader and the security programs must all share the same level of readiness.

A company’s readiness may be affected by many factors – budget, leadership and culture among them. If the company has low organizational readiness, it doesn’t mean the company needs to change; instead, the security plan may need to change to work with the company to provide the best programs possible under the circumstances. Organizational readiness often changes based on the success of the organization. If the company is successful, the right leader can create the right programs and security responses, which ultimately changes the overall threat picture drastically.

To align with the readiness level of their organizations, security leaders must understand the company’s risk appetite, management’s awareness level and the drivers of security programs. He or she must understand the forces affecting security and learn to act in tandem with them rather than making decisions in a vacuum.

Over the last six years, we’ve watched the shape of the industry changing. There will always be leading companies and very successful programs run by top leaders who are valued by management. But because of the changes in the pace and scope of business, and because of the changes in the risk picture, the group of security leaders who doesn’t fall into that top category is growing. No single skill set or attribute guarantees security leadership success, or even continued employment. Our market has become more competitive, and leaders must stay motivated, think strategically, continue learning and focus on the needs and readiness of business if they hope to continue in security leadership.

|

The Next-Generation Security Leader In 2006, the Security Executive Council identified six skill sets crucial to security leader success now and in the future: Government Elements, Security Organization Elements, IT Security Elements, Executive Leadership Skills, Business Elements, and Emerging and Horizon Issue Awareness. We have developed resources and identified recommended external resources that can help security leaders build their knowledge in each of these categories. Our newest initiative is a leader training course based on these same skill sets. If you are interested in any of these resources, contact us at contact@secleader.com. |

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!