How K-9 Programs are Force Multipliers

How do you know if a K-9 program is right for you, and how do you get started?

Meet K-9 Officer Barrett, a German Shepard and Malinois mix, and Sgt. Zachary Augustine, with the North Greenville University Office of Campus Security. You can find Barret on Instagram: @k9Barrett_ngu.

Photo courtesy of North Greenville University

NGU’s K-9 Program was implemented when Officer William Farina and Officer Stoki officially joined NGU in 2017. Chief Morris saw the opportunity to implement such a program as a force multiplier.

Photo courtesy of North Greenville University

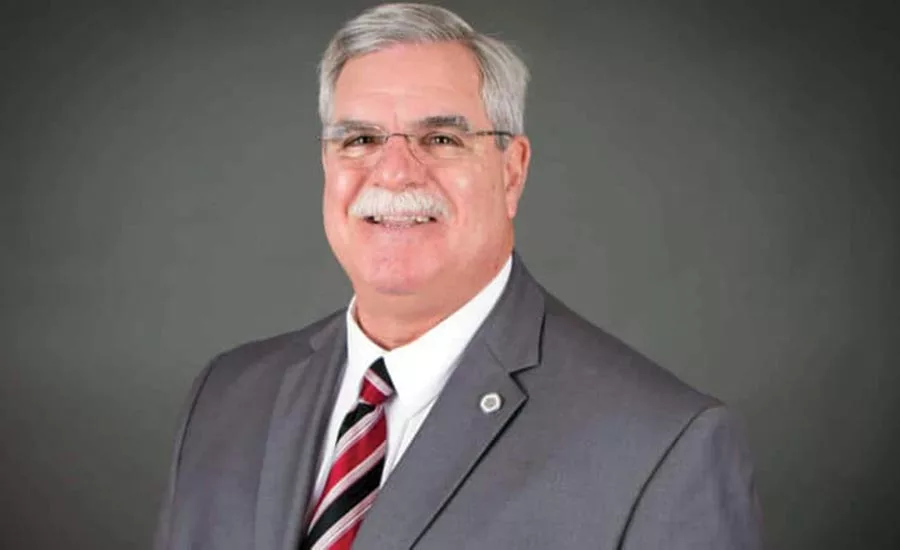

NGU’s Campus Security Chief Rick Lee Morris was a recipient of Security magazine’s Most Influential in Security in 2019. “When the K-9 is tasked for campus functions, the positive reaction is substantial.”

Photo courtesy of North Greenville University

“The bottom line is: there will be a reduction of danger or substances on a campus or organization with a K-9 program,” says Sgt. Doug Wannemacher, K-9 Master Trainer.

Photo courtesy of Will Crooks for the Greenville Journal

North Greenville University (NGU) in Tigerville, S.C. offers its more than 2,500 undergraduate, online and graduate students strong academic programs, in addition to opportunities for spiritual growth, cultural enrichment and hands-on service.

It also provides students a safe and secure environment in which to learn and live, which is due to its campus security team, led by Campus Security Chief Rick Lee Morris. Chief Morris, who has been with NGU since 2001, has grown the department from three staff members to an armed para-law enforcement agency, offering 24 hours a day, seven days a week on-duty service, protection and law enforcement. The department employs 13 full-time officers, most with specialized skills. Chief Morris was a recipient of Security magazine’s Most Influential People in Security award in 2019.

One of the daily challenges that Chief Morris and his team face is the university’s location. NGU sits on the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in S.C. and is located 18 miles away from Greenville, the state’s largest metropolitan area. “We’re in the middle of nowhere, so we have to plan accordingly for any type of interaction or any threat that might materialize,” says Chief Morris.

Even more, as with many college campuses, another challenge for NGU campus security is getting to know new students and building relationships with them. “With every graduating class, we lose a quarter of the population of the campus and replace that with younger people. Building that continuous relationship is challenging because we do not know the younger population, and with that comes risk,” Chief Morris says.

Therefore, when the opportunity arose to employ a K-9 team to mitigate some of those challenges, Chief Morris was interested. Chief Morris saw the opportunity to implement such a program as a “force multiplier,” he says. “As the campus and its census grows, the demands on our capabilities grow exponentially; hence the force multiplier aspect enters into the equation. One trained dog can replace an officer. I’ve come across many situations in this town where as soon as the dog is out of a police vehicle, it gets people’s attention and brings stability to that dangerous situation.”

Meet K-9 Officer Barrett

NGU’s K-9 Program was implemented in 2017 when Officer William Farina and K-9 Officer Stoki joined the NGU Office of Campus Security. Farina has been an Officer for 25 years and a K-9 handler for 11 years.

After K-9 Stoki retired, K-9 Officer Barrett joined the department to work with Sergeant Zachary Augustine, his official handler and trainer, who started as a Patrol Officer at NGU more than three years ago. K-9 Barrett is a German Shepherd and Malinois mix, and he is certified by the North American Police Work Dog Association (NAPWDA) in Patrol and Narcotics.

A key part of the NGU K-9 program is a partnership with the Greenville County Sheriff’s Office’s Canine Services Unit and Sgt. Douglas Wannemacher, who is a Master Trainer with NAPWDA and who has been involved with K-9 programs for more than 17 years.

“It is pretty significant to be included in the training with Sgt. Wannemacher as we are not a sworn department,” Officer Farina says. “Being allowed to work alongside sworn officers adds a high level of professionalism and adds more resources and education to our program. He has helped train both my dogs, and has helped Sgt. Augustine with Barrett.” Aside from being a critical component of NGU’s K-9 Program, Sgt. Wannemacher has assisted many organizations in implementing their own programs and in training K-9 Officers and handlers.

Since its inception, the K-9 program at NGU has been deemed a success. First, the tracking ability of the K-9 in a rural setting such as NGU is invaluable, as a wilderness search can quickly generate many man-hours, not to mention the impact on a small department’s budget. “In that setting, the K-9 can be deployed and used as effectively as eight to ten officers,” Chief Morris says.

In addition, according to Officer Farina, K-9 Officer Barrett has added location and threat awareness to security operations and has helped mitigate threats that may come with NGU’s remote location. “Having this program adds tools to our arsenal and helps us, as officers, be better prepared to deal with threats. A K-9 dog is one more officer in any situation. Having more visibility and more bodies in a situation always helps fight threats,” he says.

Drafting a K-9 Program Framework

Before getting started with developing a K-9 security program, it is important to establish the goal of the program, in addition to understanding all state and federal regulations. “The best way to start your program is to build your foundation on a rock,” says Wannemacher. “That means starting your K-9 program with the best product you can get: a strong and highly-trained dog.” Starting your program with a handler or dog that is weak is a liability to any organization.

Next, draft a framework where all duties, responsibilities, policies and practices are detailed.

Chief Morris, for instance, drafted a framework to guide commanders, officers and canine handlers at NGU. The guide served as a “selling-point” for the administration, as Chief Morris demonstrated he had the tools to reduce any liability the K-9 program might face. NGU’s K-9 framework, which could serve as a guide to other universities looking to start a K-9 program, includes:

- Detailed duties and responsibilities of the Office of Campus Security, which includes the Administration and the Canine Handler.

- Procedures in case of injury to the Canine Handler.

- Procedures on dealing with threatening animals.

- Training requirements

- Requirements on the Documentation of canine employment.

- Additionally, in the framework, Chief Morris suggests having a clear understanding of what the canine unit will respond to. At NGU, the K-9 responds to:

- Alarm calls

- Burglaries in progress

- Robberies in progress

- Felonies in progress

- Incidents where suspects are believed to be armed

- Incidents where tracking, area searches and building searches for fugitive suspects are involved

- Any suspects who are combative or pose a physical threat that could lead to serious bodily injury

- Any incident that the handler believes a canine may be helpful

- Help in the service of warrants

- Public relations such as canine demonstrations

- Large crowds

The framework also provides a section on the “Use of Force,” which notes that the canine may be utilized under the same conditions as an officer. The canine handler should consider the following before deploying the canine:

- Reasonable belief that the person poses an immediate threat of violence or serious harm to the public, any officer or him/herself.

- The individual is physically resisting arrest by means of use of force or attempting to evade arrest by flight; and use of canine appears necessary to prevent injury to the officer.

- The individual is believed concealed in an area where entry by anyone other than a canine would pose a significant threat to the officer.

It is also critical to engage the canine unit in continuous education. For instance, Sgt. Augustine and K-9 Barrett have scenario-based and maintenance training every Wednesday with Sgt. Wannemacher. “If the dogs start to get lax in one area, we start maintaining them because dogs are creatures of habits. We have to keep them at their peak performance, as they are no different from athletes,” he says.

NGU’s canine teams must be certified officers who obtain specialized training in canine operations through a certified training program or national certifications such as NAPWDA, NLECO, SCPK9A, NNDDA, NPCA or other recognized organizations, as well.

A minimum of 20 hours dual-purpose (patrol/narcotics) training and a minimum of 10 hours for single purpose training is required monthly. In addition, all dual-purpose canines must have certifications that include patrol, such as obedience, aggression control, area search, building search and evidence/article apprehensions.

Even more, Officer Farina and Sgt. Augustine say the K-9 program is instrumental in building and maintaining a good relationship with the NGU students and community. “Being able to build personal relationships with people, students and the community around us is important to our security operations and daily work with Barrett and the K-9 program,” Sgt. Augustine says.

Sgt. Augustine adds that the K-9 program also has been a deterrent to many past drug incidents. “The number of narcotics have decreased on campus since the program began,” Sgt. Augustine notes.

The abilities of the K-9 are added benefits as well, says Chief Morris. “The dog is agile and quick. The mere presence of the dog when deployed can de-escalate a situation quickly. The bark alone can bring compliance. More than 97 percent of the work performed by the dog is accomplished with their nose and only the dog can perform that task,” he says. Data shows that officer injuries decrease when the dog is deployed, as suspect compliance tends to improve, Chief Morris says.

For example, within a few weeks after K-9 Stoki was deployed, “reports of marijuana use, i.e. reports of odor, foot traffic or visualization, decreased,” Chief Morris notes.

“K-9’s are an attention-getter,” adds Chief Morris. “It gives you a higher level of professionalism and sets you apart from other security programs.”

Making the Investment

To establish a successful K-9 Program, says Sgt. Wannemacher, first you need to understand if a K-9 program is right for your organization. “You have to look at what you’re hoping to accomplish with a dog. Look at your threats, and the dog’s job description. Does the job description fit the threats you’re trying to mitigate?”

In addition, you need committed officers and a committed department, and a “handler who’s willing to put in 600 hours of training for the full patrol dog, 3-6 months to get certified, the time to do the research and an administration who is willing to supply the funds and resources, as well,” says Sgt. Augustine.

Dogs can do multiple things, adds Sgt. Wannemacher, so it is important to have an idea of what you want the dog to do for your organization. These can include narcotic detection, accelerant detection, explosive detection, aggression control or utility work, where they search or apprehend humans, or search and rescue, for human remains detection or live find for missing persons. “You must have a job description of what you want your K-9 to do before you start your program or decide if it’s right for you. That is key to a successful K-9 program,” he says.

With any security program, “You’re looking to reduce crime by being visible,” Sgt. Wannemacher adds. “When you have a marked vehicle that says ‘K-9’ on it, people understand that dogs can smell better than people do, so if they’re hiding contraband, they will get caught. The bottom line: there will be a reduction of danger or substances on a campus or organization.”

Chief Morris sees the K-9 Unit as an easy sale after the right dog has been chosen for the right environment. “In our case, it is a natural progression in the growth and advancement of the office. It provided another level of protection to not only the campus community at large, but officer safety has been enhanced, as well,” he says.

“A big plus is the PR factor,” adds Chief Morris. “Both Stoki and Barrett are well-known and greatly appreciated members of the campus community. When the K-9 is tasked for campus functions, the positive reaction is substantial. The fact that NGU has chosen to invest in a program that enhances the overall safety and security of their loved ones get the community’s attention. This investment speaks volumes about the institution’s commitment to their security operation.”

Sgt. Wannemacher also contends that a K-9 program is a “PR gold mine.” “When I bring a dog in, people open up to them. We start getting a positive reflection of our organization and a positive reaction to the program. It shows people that K-9 Officers are targeted tools, and that’s what we use them for.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!