Tools of the Master Planning Trade

Constructing a security master plan calls for a lot of homework including the essential need to know the existing and future needs of the enterprise.

Meeting with security staff and management colleagues is an important way to gather information as part of putting together a master security plan.

There is a certain level of expectation toward security. But increased levels of security can be expensive. Today, almost no one can afford to be without a security program or plan. That is not to say that the Mom and Pop grocer on the corner needs the same level of security as a global manufacturing giant; nor the single story suburban office park the same as the signature high-rise in a major metropolitan downtown area.

Security plans must be based on and balanced against the risks an organization faces.

Very few organizations have the resources to take their security program from “zero to 60” immediately. By creating a master security plan, an organization has the ability to customize implementation to meet resources. Through periodic audit of the plan they have the opportunity to customize their security program to meet evolving threat environments. The master plan, therefore, is a living document able to respond to today’s dynamic world.

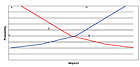

Here’s a decision model chief security officers can use when forming a master plan. Take a tough look at issues comparing probability to impact.

WHAT’S A MASTER SECURITY PLAN?

Master planning is a well-known concept in many circles. Architects will create a master plan for a new building site. IT professionals create a master plan for a new network installation or for the network disaster recovery process. The master plan is a road map to implementing any complex operational program in today’s businesses and institutions.Security has become one of those complex programs.

The security program of an enterprise must be able to swiftly address sudden and unforeseen events impacting the organization and/or its personnel while not significantly impeding the organization in its normal daily activities.

The security staff at Acme Widget Manufacturing Company mans the various entrance doors and generally observes the comings and goings of everyone in Acme’s flagship factory. Security makes everyone slow down a bit and show their company identification. Visitors must stop and register at the security desk before getting an ID badge to go inside.

Acme is notified that the United States Department of Homeland Security has raised the general threat level from Yellow to Orange. Security now implements its “Orange Plan” which requires all visitors must have everything they carry searched and wait until an Acme employee comes to the lobby and escorts them into the building.

Every security program should be able to adjust to meet changing threats to the organization -- adapt when the Department of Homeland Security changes the national threat level from Yellow to Orange to Red and back again.

Every security program needs to address the differing threat levels that exist at the same time within an organization. For example, the marketing department’s five-year marketing plan may require a different level of protection than the facilities department’s five-year capital plan.

For these reasons, the master plan is a process rather than a project.

A master plan consists of the assessment of the organizational needs, the plan to address those needs, the implementation of that plan and the continual testing or review of the implementation to ensure it continues to address the dynamic needs of the organization.

Another issue that calls for the security master plan is cost. Many organizations cannot afford to take a security program from “zero to 60” in one shot. A master plan helps to identify the critical issues and allows management to phase in the program’s implementation based on a published set of priorities.

RESOURCES

The development and production of a master security plan is not the time to discount available resources. Remember that co-worker or associate who said, “If there is ever anything I can do for you…”? That time has arrived.During the early part of the 17th Century, the English poet John Donne wrote; “No man is an island.” He could very well have been describing the master planning process for security. Use the resources that are available to you and then find more. To do justice to a plan that will guide your organization’s security for the next five to ten years will require significant investment of your time. If you have a security staff, whether contract, proprietary or a blend, use them as a prime resource. Another option is to hire a consultant who can dedicate the time and resources to produce a master plan with inputs from you and your organization.

“Master plans are road maps to implementing any complex operational program in today’s businesses and institutions. Security has become one of those complex programs,” said Kurt Collins.

DEVELOPING THE PLAN

Before you can determine what type of security plan you need to support your organization, you will need to assess where you are today and where you need to be over the initial life of the plan.Where you are now is simply a snapshot in time of the organization and its security program. This is sometimes a painful process. You need to identify your current strengths as well as your current weaknesses. It requires a critical, unbiased view of the current operation.

Where you are going will require conversations with other executives within the organization. What is the strategic vision for the next five to ten years? Where is the organization going as a whole? What changes must be made to accomplish the vision? Will new offices be opened, or will offices be consolidated? Are there plans to take the organization global? Plans to expand into new markets? How can the security function support that vision?

What is the intended life of the plan? This drives the schedule of implementation for the master plan. The life is often driven by the organization’s funding profile. How much can the organization afford to fund the first year? The second? Can the complete implementation be funded in three years, five years?

What security risks does your organization face? Are your products subject to tampering? Theft? Does a competitor want your intellectual property? Do your employees travel to risky areas of the world? And how much of that risk can be tolerated as a cost of doing business? Knowing this will help define the amount of protection or mitigation that will be assigned to each risk.

For example, Acme Widget Manufacturing Company uses a two-step process to make its widgets. Each step is automated. The machine that performs step one is a very expensive piece of equipment but is very popular in the widget industry and is therefore plentiful in the marketplace. The machine that performs step two, however, is an inexpensive machine that Acme custom builds in-house. This is what give Acme its competitive edge; but there is only one in existence and each takes about six months to assemble.

Is Acme willing to absorb the additional cost incurred by the loss of the first machine or the delay in production of the loss of the second? This answer will help allocate security money.

The accompanying chart shows a simplified decision model to assist in allocating resources to address security risk.

Incident “A” is a common problem (high probability) but has very low impact on the organization. This type of incident is not worth a high commitment of resources to mitigate.

Incident “B” carries catastrophic impact to the organization but is extremely rare or impossible. Unfortunately, the impossible has a bad habit of becoming possible. The incidents that fall in this part of the chart must be given the hardest of scrutiny, and decisions as to the level of resources to be committed must be made.

Incident “C” has a low impact on the organization as well as a low probability of occurrence. Since this event is not likely to happen, nor is anyone likely to notice if it does, it is a bad choice for the allocation of resources.

Incident “D” is a highly likely event that carries catastrophic impact such as a major earthquake or firestorm in California. While things are done to try to mitigate this type of event, these are not typically ongoing programs. A lot of resources are invested in recovering from this type of incident.

Incident “E” is where the majority of the security resources are allocated. This is the “Critical Impact Area” for the organization’s security risk. The risks that fall into this area of the chart are at the right balance between criticality and likelihood that investment in their prevention and mitigation are likely to show a positive return on the investment.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!