Building Safety: It’s in the Card

And since the World Trade Center tragedy, building owners, managers and first responders now seek extra help such as the Building Information Card, developed by the New York Fire Department.

These fire brigades participate in ongoing training and evacuation drills operating on an up-to-date building fire plan approved by the local fire department. Tenants also can appoint a fire warden responsible for organizing an emergency team on each floor – who in turn coordinates emergencies and evacuations.

Meanwhile, the tenants themselves participate in evacuation drills and periodic life safety training. A good fire safety program teaches its tenants basic building life safety systems, including stairwell egress, which are then tested on a monthly basis. The building security vendor should have trained first responders, and that training documented.

Part of that training includes use of the building’s public address system and the establishment of a system for communicating beyond the premises. Fire safety professionals encourage building managers or owners to establish a liaison with their local fire department and invite first responders to tour the facility and familiarize themselves with the building layout and life safety systems. Providing critical building information and floor plans to fire department first responders could also pay off well in the event of an emergency.

Security versus life safety

The standard of care required for fire safety is higher than for security issues. Whereas providing a secure environment for tenants should be considered equally important, building owners have a legal duty to protect tenants and visitors from harm due to fire emergencies. The building owner may hire property management and security companies to fulfill this requirement so long as those firms can provide a life safety program in accordance with the local fire code.The legal definition of this requirement obliges a reasonable response by the building owner to protect occupants from harm. Property managers have a duty to discover if criminal or negligent conditions exist on the property and either provide sufficient warning for tenants to avoid harm, or remove the threat from property. What constitutes a reasonable response relies largely on the local environment; if the property, for example, has a history of criminal activity at or near the premises then such related hazards are considered foreseeable.

According to a 2002 survey by the Building Owners and Managers’ Association, fire safety and emergency preparedness represented the two greatest priorities for property owners and managers. Some of these concerns are legal; under fire codes, properties are usually subject to annual fire system inspections and monthly testing of life safety systems. Providing a copy of pertinent sections of the fire plan to each tenant can also help management meet these priorities.

Management also can address these concerns by appointing a fire safety director (FSD) to oversee a building’s life safety program, supervise the fire brigade’s training and ensure that team is competent to carry out building evacuations. An FSD typically coordinates tenant life safety training and fire drills.

Building owners should submit a written evaluation of the final fire drill evacuation plan to their fire wardens, keeping a copy on file with their documented life safety system testing. These monthly system tests normally include stairwell egress, stairwell emergency lighting, stairwell pressurization, stairwell intercoms and emergency generators, but certain building-specific considerations can be tested as well. Federal law requires all written records to be available for review by fire department officers on the premises.

Training

The National Fire Protection Association’s Fire and Life Safety Code requires buildings to have a trained fire brigade ready to respond to fires and assist with evacuations. This fire brigade may consist of building staff, including security and engineering personnel, and must be familiar with life safety systems including fire alarm, public address system, elevator control panel, stairwell egress control, smoke evacuation and stairwell pressurization systems.Tenants must appoint a fire warden and emergency team for each floor. These team members must be familiar with evacuation procedures and response to other types of emergencies, as well as conduct annual evacuation drills and periodic life safety training for their respective floors. Drills and training must be documented by property management, and disabled tenants should be identified and accounted for in evacuation plans.

Staff should also be familiar with responses to other types of emergencies, including bomb threats, medical emergencies, power failures and elevator entrapments. After Sept. 11, property managers also developed terrorism response plans that account for anticipated chemical, biological and radiological threats. Like fire safety, a key issue in developing a successful anti-terrorism strategy is a liaison to and communication with local and federal authorities.

Fire plan

Fire codes require building owners to submit an official plan to the fire department for approval. This fire plan, which provides detailed instructions for the fire brigade to follow in event of an evacuation, should be reviewed at least annually and updated when warranted. It includes duties and responsibilities for the FSD, fire wardens, tenants and fire brigade. Plans also should detail evacuation policy, life safety training, fire drill frequency, plan distribution, reporting fire alarms, documentation, special instructions for mobility impaired, public address announcements and life safety system maintenance.

Some jurisdictions additionally require building owners to plan for non-fire emergencies, including, among others, severe weather, bomb threats, power failures, work place violence and chemical biological response.

High rise best practices

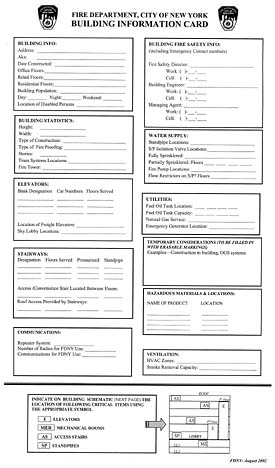

In the wake of Sept. 11, the New York Fire Department developed what became known as the building information card (BIC), a laminated card kept in the fire control room in high-rise buildings that provides first responders with critical building information needed during an emergency. The two-page, laminated, 8- by 14-inch card, located at the ground floor fire panel, lists building life safety systems, communication, utilities, water, ventilation, elevators, stairwells and emergency contact numbers. A building schematic shows the building stacking plan, and lists critical locations and egress points.

Reports concerning several notable high rise fires (see sidebar) demonstrate that building management and fire department first responders, in each case, were repeating the same mistakes. Their fire brigades were not properly trained. Security staff delayed the all-important call to the fire department. Stairwell doors were locked. The fire department was unfamiliar with the building. Each fire plan was altogether inadequate for dealing with the emergencies these buildings faced. Adding a building information card, similar to that developed by the New York Fire Department, provides yet another way to better communicate during emergencies.

Sidebar: Lesons Learned

- Fire Brigade not Trained

- Delayed Call to Fire Department

- Stairwell Doors Locked

- Fire Plan Inadequate

- Fire Department Unfamiliar with Building

Sidebar: Metro Fires Burn Into Memory

High rise fires in Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles have been influential in bringing the need for better security and life safety to the attention of building owners, security executives and local authorities with code jurisdiction.

2003 – Cook County Administration Building – Chicago

An article in the June 2004 issue of Security magazine goes into some depth on the lessons from from this high rise incident which killed six people.

1991 – One Meridian Plaza – Philadelphia

February 23, 1991, at 8:23 p.m., a smoke detector is activated on the 22nd floor. The alarm monitoring service calls the guard desk and is informed that a building engineer is investigating the alarm. The fire department is not called; rather, the building engineer takes an elevator to the 22nd floor to investigate. When the elevator doors open the engineer is trapped by heat and heavy smoke. A security guard in the lobby hears the engineer’s call for help and recalls the elevator to ground level, saving his life.

A passerby seeing smoke coming from the building uses a pay phone to call 911. Philadelphia Fire Department arrives on the scene, but security and engineering provide firefighters with limited building information. Stairwell doors are locked; firefighters have to force them open, causing smoke to fill the stairwells above the 22nd floor. A complete power failure and improperly installed standpipe valves contribute to the fire department’s inability to put down the blaze Three firefighters radio for help, stating they are on the 30th floor with their air supply running out. Three hundred firefighters evacuate the building due to risk of structural collapse. The fire burns for 19 hours completely consuming eight floors, ending only when automatic sprinklers are activated on the 30th floor. The cause of the fire was determined to be from a pile of linseed oil-soaked rags left on floor 22 by a contractor. The bodies of the three firefighters who had radioed for help were later found on the 28th floor.

1988 – First Interstate Bank – Los Angeles

On May 4, 1988, at 10:25 p.m., contractors working on the 5th floor see smoke and pull a manual alarm. A security guard in the ground floor lobby silences the alarm. The fire department is not called. At 10:36 p.m. smoke detectors are activated from the 12th to 30th floors. A building engineer takes an elevator to the 12th floor to investigate the alarm and becomes trapped as the elevator doors open. Security personnel call the fire department after losing contact with the engineer, a full 15 minutes after the initial alarm.

The sprinkler system and fire pumps had been shut off pending installation of water flow alarms. The fire destroyed five floors, injuring 35 occupants and 14 firefighters. Ultimately, 380 firefighters were able to extinguish the fire by attacking it from all four stairwells. The investigating engineer perished.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!