Protecting Students, Staff and Community at Marymount California University

Learn about Hector Rodriguez, Director of Public Safety and Security at Marymount California University.

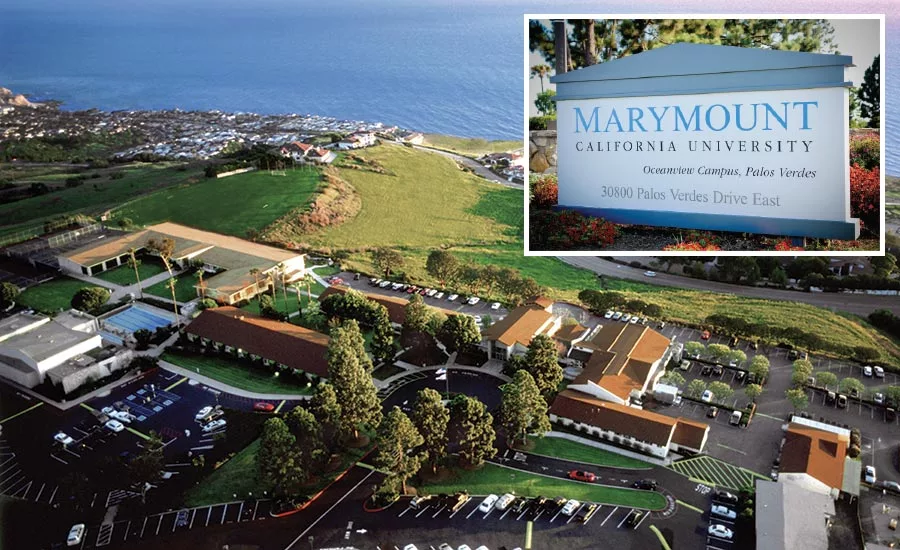

“Marymount California University (MCU) possesses some of the most breathtaking vistas of university campuses: its Oceanview Campus encompasses 26-acres that overlook the Pacific Ocean and Catalina Island in Rancho Palos Verdes, California.”

Photo courtesy of Marymount California University.

“Our scope is wider: it is public safety, which means addressing all concerns with students feeling safe on this campus,” says Hector Rodriguez, Director of Public Safety and Security for Marymount California University.

Photo courtesy of Marymount California University.

Marymount California University (MCU) possesses some of the most breathtaking vistas of university campuses: its Oceanview Campus encompasses 26-acres that overlook the Pacific Ocean and Catalina Island in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif., located about 25 miles from downtown Los Angeles. It is as peaceful as it sounds and looks, and its low-crime statistics reflect that.

“We are mostly crime-free, but we still communicate security’s value to ensure we remain crime-free by addressing any potential threats before they become a crisis or emergency,” says Hector Rodriguez, Director of Public Safety and Security for MCU. He is responsible for emergency and disaster management, crime prevention, parking and traffic enforcement, security escort services and property patrol. He, along with his team, help ensure the safety and security of the MCU campus, The Villas, where students reside, up to 940 students, faculty, staff, as well as many more aspects of MCU.

Rodriguez has more than 29 years of public safety experience. Previously, he was Lieutenant, Deputy Chief of Police for the Los Angeles Unified School District, Chief of Police for the Santa Ana Unified School District and a Public Safety and Education Consultant. He has overseen K9 operations, firearms training, traffic safety and technology units. Rodriguez is a graduate of the FBI National Academy, as well as the Los Angeles Police Department’s West Point Leadership Program. He received a high ranking in the L.A. School Police Department, which gave him many insights on engaging in security practices at a campus, ultimately preparing him for his current role at MCU.

“Education has always been a part of my life,” he says. “To be in an environment where learning is taking place, where young people come to discover their place, it is invigorating and exciting. There is a lot of activity here, and it takes me back to my own college days where I experienced those same feelings of freedom and liberation, learning and understanding the world better. It’s a great place to be.”

Ensuring students experience freedom comes with substantial responsibility, notes Rodriguez. “Many of the risks and challenges we encounter here are driven by the violence and crises people see on television or online,” he says. “One of the biggest concerns in higher education is keeping up with the flow of information on school safety practices, reviewing recent incidents, and learning and extracting value from those incidents to help better inform and influence current security practices in our campus. Our job is to keep up with the best security practices and to respect students while looking out for them. To ensure their safety, we must consider reality as uncomfortable as it is. “Unlikely to occur” is not the same as ‘never going to happen.’ This applies to any place where large groups of people meet, regardles of how safe we perceive them to be.”

Rodriguez and his team of 13 security officers are a collaborative effort, he says. “Safety is really a shared and collective responsibility, so we partner up to keep open the lines of communication within the departments here and in campus. This helps ensure that we all understand safety practices and the principles that come with those practices, and it also helps address any concerns before they can potentially grow into serious or violent acts,” he says.

Partnerships and Initiatives to Ensure Safety

As part of maintaining an open line of communication, Rodriguez engages with local law enforcement and first responders in fire drills, active shooter presentations and other emergency response trainings and exercises. “The Oceanview campus sits in the L.A. Sheriff’s jurisdiction and the housing unit, The Villas, sit in LAPD’s jurisdiction, so we need to leverage those partnerships because law enforcement and first responders will be responding to any crisis on campus,” he says. “Keeping those lines of communication help security staff and students understand how to respond to any crisis and find ways to address threats before they actualize.”

Nobody wants to think about worst-case scenarios, says Rodriguez. “Being in law enforcement, I was taught to think of the worst-case scenario. Due to the relatively safe campus we have, you need to find a way to present that reality and that threat possibility without alarming people,” he says. He and his team train staff on Stop the Bleed, provide presentations on active shooter scenarios and more crisis management scenarios.

One of the most difficult parts of his job is dealing with finite resources as he would like to do a lot in terms of educating and training, he says. “We have the full support of the university, but we deal with constraints, as well. The difficult part is understanding that we cannot do everything, and we probably shouldn’t do everything,” he notes. “After every active shooter news report, for instance, people come up with many solutions impulsively. Every violent incident is complex and unique. There are no simple solutions with respect to preventing these occurrences. We need to take a step back and really think about what solution will be both effective and reasonable. We certainly have to take appropriate measures, but we don't want to overreact.”

“Given a finite amount of resources, my job is to find solutions that are effective. To get to that place, I review numerous resources and information before I am confident those solutions, practices or strategies will make a difference. We need to make sure our efforts are spent on the right solutions that will effect change for the better.”

For Rodriguez, finding the right practices that make a difference led him to develop a Threat Assessment Team, comprising a mental health counselor and more counselors on campus, the Vice President of Student Affairs and himself. “It is a multi-disciplinary approach to addressing and assessing threats,” he notes.

“In my search for the right solutions, I found it is critical to look at potential active shooter events from a viewpoint of: How can they be prevented?” he says. “And threat assessment is a critical component of prevention. When you dissect these incidents, you find that most of them are not random. There are things that led up to an incident, and the signs are everywhere. People need to be aware of the signs, so they must be trained on how to assess the possibility of threats, which includes looking at behaviors, practices, tendencies and concerns before they become a crisis.”

In addition, the Threat Assessment Team encourages students to take a proactive approach to identifying risks, engaging in communication and remaining vigilant, as well, says Rodriguez. “I have my own perspective coming from law enforcement, but I also need to hear how mental health influences threats and risks, and to have a better approach to addressing risks.” Although the Threat Assessment Team has not been needed, Rodriguez is “thankful” that it is in place.

Another initiative Rodriguez has undertaken is enhancing the camera system. “We now have more spaces on campus that are covered by our video surveillance system. We focused on implementing video surveillance where students congregate and where we thought they would be most useful, such as hallways, cafeterias, large meeting rooms, the auditoriums and The Villas.”

It has been a great way of leveraging all resources, he notes. “The camera system combined with our security presence has been an added benefit. No cameras are located in places where there is an expectation of privacy, so it provides reassurance to students that we are looking out for their well-being, as opposed to monitoring them.”

As the budget allows and improves, he hopes to continue to enhance the camera system and to implement other measures. “Currently, we have two officers here who have experience serving as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs). We are looking into cross-training more security officers as EMTs, recognizing there is a need for Stop the Bleed if a crisis was ever to occur. Our staff needs to know how to provide trauma care before paramedics arrive, in order to save lives.”

Measuring Security’s Value

Parents and students drive the perception of his security brand, notes Rodriguez, which is influenced by MCU’s low crime statistics. “We are very vigilant and continue to train our staff to monitor threats. We continue to raise awareness among students, so that they are well-informed to address and tackle any threats.”

In the year and a half that Rodriguez has been at MCU, Rodriguez has seen many parents and students visit the campus. “I engage with the parents, and when they see me in uniform, they are very thankful and relieved to see a security presence in campus. It is what makes this campus attractive. If you find a way to make it safe without students feeling oppressed, that’s where the value comes in.”

Overall, working as a School Resource Officer in a School Police Department, Rodriguez learned that “you get more done by enhancing the communication and by creating a safe environment where that exchange of information can take place,” he says. “Our job is more than just enforcement. In fact, if you are not a sworn officer on campus, your focus is on enforcing policies, not the law. Even if we had a fully sanctioned police department, our scope is wider: it is public safety, which means addressing all concerns with students feeling safe on this campus. That means focusing on preventing threats.”

Rodriguez has three key pieces of advice for security leaders working in higher education:

- Hire the right people. Ensure the person hired is the right fit for the university, and that he or she understands higher education and the environment. “Many times, when we sell police or security services, we tend to oversell the active shooter response side, and that’s important. But most of what happens day-to-day is engagement, looking out or identifying behaviors, and addressing issues before they become problems. In order to do that, with any degree of efficiency, you have to be personable, engaging and approachable to students,” he says.

- Train in Threat Assessment to prevent any crisis. Ensure everyone, not just security staff, are trained in identifying and addressing potentially violent behavior before they progress into a crisis.

- Have a crisis response for a multitude of emergencies. The plan should include active shooter response, he says. “People should have basic knowledge on what the procedures are when a crisis ensues. “It’s important to find the time to practice and train everyone on basic principles of crisis response,” he notes.

Last, but not least, Rodriguez says a key, but very important challenge is to learn how to create a safe environment, without creating anxiety for both staff and students. He says, “Learning how to balance those two is critical to working in the higher education sector.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!