Money and Terror: How the Financial Sector is Hitting Back Against International Crime

In the wake of 9/11, the U.S. Treasury was given the green light to go after rogue banks and terrorism profiteers. Now, how can private sector businesses join the fight?

Juan C. Zarate is the Chairman and Co-Founder of the Financial Integrity Network, the Chairman of the Center on Sanctions and Illicit Finance, a visiting lecturer of law at Harvard Law School, and a senior adviser to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He served as the first-ever Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorist Financing and Financial Crimes for President George W. Bush and later served as the Deputy Assistant to the President and Deputy National Security Adviser for Combating Terrorism (2005-2009).

On 9/11/2001, Juan Zarate was the new senior advisor to the Undersecretary of Enforcement at the US Treasury Department, just three weeks into his role to work on international money laundering and national security cases.

His office gave him a view of the Pentagon, and he saw the smoke from American Airlines Flight 77 that hit the west side of the building, killing all onboard the airplane and 123 on the ground.

“I realized that this is war, that we’re all going to need to adopt wartime thinking, and that the Treasury Department was going to have a more important role in that,” he says. “In terms of mission and the focus of the Treasury Department, everything shifted dramatically. President Bush was asking the Treasury and all the key elements of the national security establishment to use all elements of their power to undermine terrorism, to prevent further attacks and to dismantle support for those terrorist networks. Our focus immediately became one of more creative thinking about the use of financial intelligence, how we would expand the regulatory system for terrorist financing and money laundering purposes, and how we thought about and leveraged our tools and relationships both within the United States, within the federal government and then with our foreign counterparts. Treasury now had to play a role in figuring out how to deny terrorist groups and their state sponsors the ability to access capital, access the financial system, and move money and resources around the world. How could Treasury make it harder, riskier and more costly for America’s enemies to raise and move money around the world? That was our mission.”

Ultimately, Zarate and his colleagues, through the creation of the Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, began using more financial intelligence, more sanctions and new regulations provided in the Patriot Act, including the so-called “Section 311” that has the effect of transforming a target bank or institution into an overnight pariah. In today’s financial world, where New York and the United States dollar remain of paramount importance, “hitting” a bank with a Section 311 finding that locks it out of the U.S. financial system can be devastating and serve as a deterrent for other banks. A 311 can destroy a rogue bank that was a conduit for illicit money flows involving, for example, al-Qaida or Iran.

For example, one example of Section 311’s uses and limitations, is the story in Zarate’s book, Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare, of the Treasury Department’s assault, beginning in 2005, on North Korea, which American officials said was involved in activities like counterfeiting and drug trafficking. In the book, Zarate describes how the United States hit one of the banks it linked to North Korea, Banco Delta Asia in Macau, with a Section 311 regulatory action. Soon, banks throughout the region began turning away or throwing out North Korean government business. By this one simple regulatory act, Zarate writes, “the United States set powerful shock waves into motion across the banking world, isolating Pyongyang from the international financial system to an unprecedented degree.

“And through expansion of the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act that means more sectors of the financial community are now subject to principles of anti-money laundering and related requirements,” Zarate explains. “We created greater visibility and accountability for what was happening in the financial system. We engaged in much more financial diplomacy with central banks, finance ministries and even the major global banks around the world, and in concert with other parts of the U.S. government, we enforced regulations, laws and actions in a much more aggressive way.”

Ultimately, he notes, there are only so many tools in the financial toolkit and they must be used in concert with other types of power to be effective. “Sanctions are a visible and powerful set of tools, but they can and should complement our diplomacy and our military action. They can give greater reach to our law enforcement and depth to our intelligence. We now have a playbook for how these tools are used to advance our national security interests across the board.”

Turning Point

Zarate has dedicated most of his career to thwarting terrorism and its radical ideologies. He started as a federal terrorism prosecutor in the late 1990s, assigned to cases involving al-Qaida, Hamas, FARC, and suspected domestic terrorists. In 2005, he was asked to serve as President Bush’s Deputy Assistant and Deputy National Security Advisor for Combating Terrorism, where he was charged with setting, coordinating and executing the nation’s counter-terrorism strategy and dealing with all transnational threats – from hostage-taking to piracy. He served in that role until the change in administrations in 2009, and helped with the transition to the Obama Administration.

Now, Zarate is the chairman and co-founder of the Financial Integrity Network consulting firm, the chairman and senior counselor for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies’ Center on Sanctions and Illicit Finance (CSIF) and a visiting lecturer at Harvard Law School. Among other positions he holds, including a place on the board of the Vatican’s Financial Information Authority, he also serves as a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and a senior fellow at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

Among Zarate’s roles in the White House was developing a strategy to counter violent extremism – the “war of ideas.” Last year, as an advisor for CSIS, Zarate helped lead a study along with Shannon Green and Farah Pandith, and a Commission co-chaired by Tony Blair and Leon Panetta. The study, Turning Point: A New Comprehensive Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism, examines violent extremism and lays out a policy roadmap for addressing the threat from the ideology animating global terrorism.

The gravamen of the study is that violent extremism has grown even more severe and urgent after 9/11 and presents a generational and global challenge. New and powerful extremist movements have taken root. Terrorist groups around the world have used technology, the media, religious schools and mosques, and word of mouth to sell their twisted ideologies, justify their violence and convince too many recruits that glory can be found in the mass murder of innocent civilians. The spread of extremist ideologies and increasingly, frequent terrorist attacks, it says, are stoking anxiety and fear across the globe.

Diminishing the appeal of extremist ideologies will require a long-term, generational struggle. The United States and its allies must combat extremists’ hostile world view with a new and comprehensive strategy – one that is resolute, rests in soft and hard power and galvanizes key allies and partners from government, civil society and the private sector.

Just as President Bush called for an all hands on deck strategy after 9/11, the same is required to prevent the radicalization and recruitment of a whole new generation, the study notes. And the U.S. government, its allies, especially from Muslim-majority countries, and the private sector have an essential role to play – providing leadership, political support, funding and expertise. The report has a specific plan, with eight major components:

-

Strengthening resistance to extremist ideologies, which includes education reform to stop the teaching of extremist ideologies in schools.

-

Investing in community-led prevention: Governments should enable civil society efforts to detect and disrupt radicalization and recruitment, and rehabilitate and reintegrate those who have succumbed to extremist ideologies and narratives.

-

Saturating the global marketplace of ideas: Technology companies, the entertainment industry, community leaders, religious voices, and others must be enlisted more systematically to compete with and overtake extremists’ narratives in virtual and real spaces.

-

Aligning policies and values: The United States should put human rights at the center of countering violent extremism (CVE), ensuring that its engagement with domestic and foreign actors advances the rule of law, dignity, and accountability. In particular, the U.S. government should review its security assistance to foreign partners to certify that it is being used in just and sustainable ways.

-

Deploying military and law enforcement tools.

-

Exerting White House leadership: The administration should establish a new institutional structure, headed by a White House assistant to the president, to oversee all CVE efforts and provide clear direction and accountability for results.

-

Expanding CVE models: The United States and its allies and partners urgently need to enlarge the CVE ecosystem, creating flexible platforms for funding, implementing, and replicating proven efforts to address the ideologies, narratives, and manifestations of violent extremism.

-

Surging funding: The U.S. government should demonstrate its commitment to tackling violent extremism by pledging $1 billion annually to CVE efforts, domestically and internationally.

For the private sector in particular, the report suggests that it has a principle role to play in the CVE domain. This involves all elements of the private sector and civil society pushing back on the manifestations of extremist ideologies in different ways around the world. This includes leveraging the private sector to prevent extremist groups from taking hold of key resources or destroying populations and historical sites. “Private security companies can help with the protection of at-risk populations and sites on behalf of the international community,” Zarate says. “Fundamentally the report is about the need for the government to prioritize this issue, but also for the private sector to be directly engaged, including from a funding standpoint,” he notes.

“The report is very powerful with its emphasis on the central role of the private sector to counter violent extremism, not necessarily the terrorist themselves,” Zarate adds. “Civil society needs to take ownership of the challenge of violent extremism, which is a threat to a range of international values, principles and goals. There’s a role for a range of private sector actors and networks – from technology companies to human rights groups – to counter extremism and terrorism,” he says. That includes ensuring the ideology of violent extremism for al-Qaida and the Islamic State never takes a deep hold or finds a reservoir of support and animation in the United States.

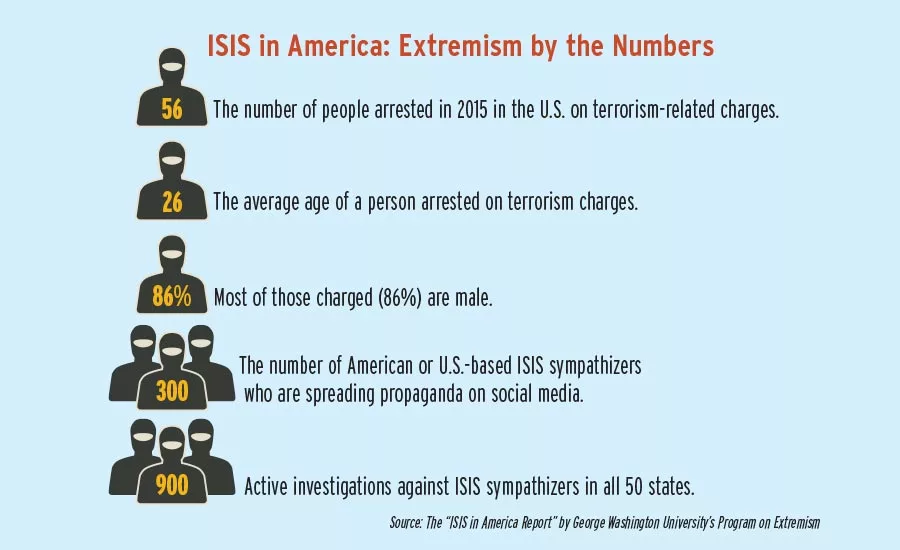

How are people radicalized? “There is no one-size-fits-all answer. Sometimes they are radicalized because they’ve reached a point of disillusionment, they’ve lost a family member or they are socially isolated, or a major event happened, and that leads to a search for identity,” he explains. “The report lays out the research on this topic, which continues to evolve. To the extent that individuals see themselves in heroic terms as part of a movement to defend fellow Muslims and to attack non-believers or infidels, they begin to identify in those singular terms. It may be that they identify more rigorously as part of a movement or part of a terrorist group, it’s the one ideology that they latch onto as they’re searching for identity and meaning in life. Terrorist groups find pockets of populations and individuals who are susceptible to their message and can be recruited and radicalized as a result. ISIS has made a practice of targeting these kinds of individuals through social media.”

“Enterprise security executives spend a lot of resources on physical security, obviously,” Zarate notes. “But are they grappling with the longer term impacts and threats from the terrorist ideology and how to counter it? This implicates issues like insider threat and threats in the environment. The private sector and civil society are critical to countering the ideology as it emerges around the world.”

As one example, he says, violent extremist have argued against polio vaccinations, and those who provide those vaccinations are seen as a foreign attempt to control Muslim populations. “The international community, from the medical community to private security, must push back and protect vaccination teams,” Zarate says, “by protecting those medical facilities and teams that provide those vaccinations, we are then countering the ideology and the effects of it.

“The terrorist ideology has to be confronted in creative ways, with resources attached to it as well as strategies with the private sector, with civil institutions, with philanthropy and with communities of interest to counter the ideology and to defeat it,” he says.

Challenging Extremism Peer to Peer

Groups like the Islamic State and Nigeria’s Boko Haram have successfully used the internet to market themselves and gain recruits, and dozens of young people from the United States have joined groups like the Islamic State.

DHS and other federal agencies have turned to the very people whom terrorist groups are trying to attract: young people.

Under the program Peer to Peer: Challenging Extremism, students at dozens of universities are given a budget of up to $2,000 each semester to develop social media campaigns and other tools to counter the online recruiting efforts of terrorist groups like the Islamic State. The competition is judged by Homeland Security and other national security officials, and the winning school is given $5,000.

Fifty teams recently participated in the spring 2017 program, with the University of Maryland taking first place for its It Just Takes One program, which sought to address the “bystander effect,” empowering bystanders from inactive to “confident to intervene” in the event they notice a loved one’s radicalization. The online forum created with their website and social media pages was designed to encourage open dialogue, while an original, online video game teaches warning signs of radicalization and constructive reaction methods.

The second place campaign from the University of Massachusetts Lowell, Project PACE, stands for Personalized Approach to Counter-Extremism Education and provides tailored educational content to their target audience to counter misinformation.

The third place team from the University of Houston, ME to WE, counters violent extremism by emboldening individual voices to dilute perceived polarized opinions about Muslim immigration – one voice (“me”) belongs to a collective whole (“we”), according to the team. More information can be found at https://edventurepartners.com/peer2peer/

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!