The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated a steady increase in remote work. Surprisingly, many organizations are discovering that concerns about potential lost productivity were exaggerated, and it’s now believed that one-quarter or more of all workers may become predominantly home-based. One of many consequences of this change is an increase in cybersecurity risks and in the complexity of implementing effective security to protect organizational information and computing infrastructure. As with pre-COVID security threats, well-proven cybersecurity strategies based on user and device authentication remain effective, and they now are more important than ever.

How prevalent is the movement to remote work? Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey shows that telecommuting (which uses technology to eliminate commuting to a workplace) was practiced by about 3.6% of U.S. workers at the end of 2018.

Two to three days of work at home is typical for this category of worker, and appears to be a “sweet spot” that balances remote duties with group activity in a traditional workplace setting. Researchers at Global Workplace Analytics estimate that post-pandemic, between 25-30% of workers may continue as remote workers, a 7X-8X increase over pre-pandemic numbers

In less than a year, a workplace perk once limited to a small percentage of employees is now utilized by a much larger group of workers. The pandemic transformed remote work from a “nice-to-have” option to a necessity. Concurrently, the pace of innovation and workforce adoption of digital tools that support remote work also advanced dramatically. With that rapid adoption, long existing risks associated with digital technology have also grown. The increased risks are prevalent across all work environments: commercial and industrial enterprise computing systems, industrial control systems and government systems.

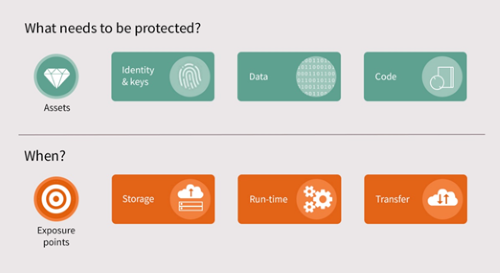

As always, vigilance by the security professionals tasked with protecting networks from intrusion is the paramount defense, and the basic formula is simple. Cybersecurity is based on defining what needs to be protected and at what points the protection is required. However, the explosive growth of remote work places new strains on the information technology infrastructure of any organization.

Figure courtesy of Infineon

Proliferating attack surfaces

A basic defense tactic is to limit the number of potentially vulnerable attack surfaces accessible to a bad actor. With remote work, attack surfaces may be multiplied. A workforce that previously accessed organizational data and code within an organization’s well-protected networks now expects the same level of access from outside of those networks. The obvious counter to this is to require access through encrypted VPN (Virtual Private Network) connections. Yet, a 2020 report from Kaspersky Labs revealed that 53% of workers say they use a VPN to access their employer’s systems when working from home.

Adding to the risk equation, many remote workers use personally-owned devices while “on the job.” Kaspersky’s 2020 report indicates that half of companies that allow employees to use personal devices for network access when working from home have no policies regulating how they may be used. An organization’s well-protected network is potentially compromised by insecure access from computers, smart phones and tablets beyond the control of the IT security team. Remote workers also are likely to share their Internet access point with family and/or friends, introducing still more non-secured devices to a shared connection.

Other pandemic-related challenges faced by security and IT professionals involve changes in supply chain relationships. Introduction of new business partners to fill gaps in a supplier network may inadvertently lead to oversights in vetting these partners and enabling secured communications links. In manufacturing organizations, accelerating digitalization of ICS (Industrial Control Systems) also is an issue. Remote management of ICS requires connectivity to many devices that previously were secured, in part, by isolation. Both of these challenges may abate to some extent as the pandemic is controlled. However, improvements to operational agility realized as business models adapt make it likely that they will become ingrained practices. Unless, of course, a future security failure causes a snapback.

Managing increased threat levels

With the trend clearly pointing to workplaces where remote access is the rule, and not the exceptional case, how can organizations manage the increased threat level? Experts gathered by MIT’s Sloan School of Management suggested several steps during a series of online panels in 2020. They began by identifying greatest areas of vulnerability, including:

- Information stealing and fake product scams.

- Ransomware and malware attacks.

- Remote work vulnerabilities, including unprotected videoconference links or stolen videoconference passwords and access to conferencing from unsecured networks.

Cybersecurity and IT professionals recommend starting with reinforcing basic security practices to adjust for a remote workforce. They note that workers should be wary of information requests and always verify the authenticity of the source; make sure that all devices with network access have up-to-date software and patches; and employ dual-factor authentication for devices whenever possible. Most importantly, experts gathered by Sloan note that even in a post-pandemic era, cybersecurity is shifting away from a perimeter-based model where all assets inside a network are trusted. Instead, zero-trust architectures, where individual, devices and applications are always authenticated and authorized before gaining access to a network, need to become the norm.

The recurring theme of these recommendations is authentication of sources, of users and of devices. In the last decade, cybersecurity professionals have reached consensus that authentication schemes should be based on a protected hardware element. The purpose of what is called a “secure element” is to provide a protected root-of-trust that can be embedded in each device capable of being connected to a network (whether a private network or the Internet). Infineon has worked in the field of hardware-based security for several decades, providing chip-based roots-of-trust for the authentication of travel documents, payment cards, smart and connected electronic devices, as well as computers and data storage systems.

As noted earlier, implementing VPN access for all remote workers is a critical step in secured access, yet it is required for just one-half of remote workers. One prevalent method today for VPN authentication involves a TPM (Trusted Platform Module), which is a dedicated, hardened security processor based on standard-compliant or standards-ready specifications. Infineon’s OPTIGA™ TPM security controllers are now common in mobile computers running Windows and Linux-based operating software, in storage devices and in industrial computing systems. Similarly, Infineon also provides solutions for cellular and low-power WAN devices, and as embedded security for product authentication and brand protection.

A remote working future

The pandemic’s impact on remote work is an acceleration of a long-term trend that will continue for many years. The evolution of remote workplaces is one of many adaptions made possible by the emergence of connected, smart devices in nearly every aspect of people’s lives. The “Internet of Things,” which is likely to enter an even more dynamic stage of growth as 5G connectivity will make it even easier to link devices together, extends cybersecurity concerns for organizations and individuals alike. Ultimately, the billions of connected devices in the Internet of Things also represent a multitude of potential attack surfaces. In the smart home of the future, remote workers may ask their smart speaker or smart TV to access files, and it will be up to cybersecurity professionals to protect their networks from access by unsecured devices. A root of trust in every device will make what some might think an impossible task possible.